By: Rehann Rheel

Frozen in Fear:

I paused where I stood and stared at the form lying on my living room couch. My brain, still slow to process information this early in the morning, slowly ticked off the things it knew I wasn’t seeing. I wasn’t seeing my mom or my aunt, because I could hear them a few yards away, in different rooms. I wasn’t seeing my sister, because she does not have man feet or such holey socks. And I wasn’t seeing some employee of my mother’s that she’d asked to house sit for the night because that didn’t even make any sense. So that meant…what I was seeing was…

An intruder.

In my house.

Sleeping on my couch.

I had to warn somebody. My sister, my mom, my aunt—and myself, of course—were all in danger. But when I tried to call out, nothing happened. Like whatever neurons connected my brain to my vocal cords didn’t exist.

Stupid, stupid.

Plan B, then. Getaway, go to the adults and warn them via the most intense game of charades I’ve ever played.

I had better success with Plan B. Slowly backing away (because I was afraid that the intruder wasn’t sleeping and that he’d leap up like a ninja the second my back was turned and stab me), I left the living room, then the breakfast nook, and finally reached the kitchen where my aunt was pondering wooden pieces on the ground; wooden pieces I knew must be from the door the intruder came through.

When there was finally a wall between me and the intruder, I got some control of my vocal cords back. Enough to rasp, “Look! Look!” as I gesticulated at the living room.

The concept of “fight or flight” is thrown around a lot—in TV, books, anything. But what I did that day—at least at first—was neither fight nor flight: it was freeze.

The Science of Fear:

Fear is a not-so-dear friend of mine. You see, I am an easily startled person, and can hardly make it a day without being scared by some unexpected sound or presence. But despite my frenemy status with fear, I don’t actually know how it works. Turns out, fear is an extremely complicated, multi-step process that happens in less than a second.

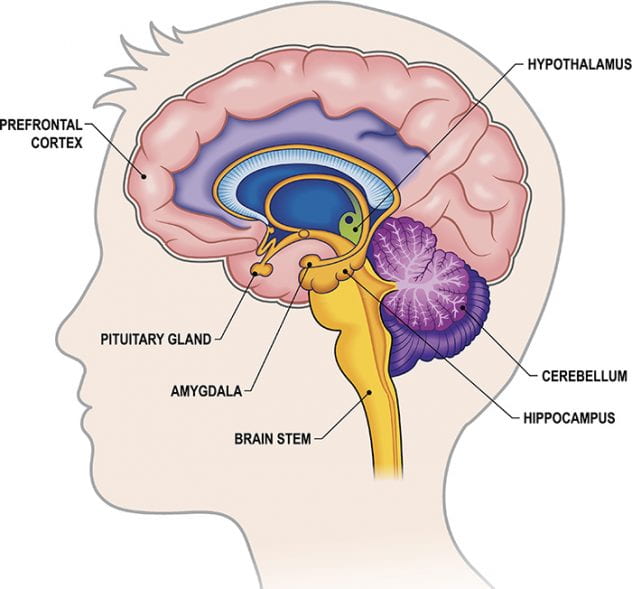

First, comes the object of fear. Maybe it’s a speeding car or a murder hornet or just a strand of hair you thought was a spider because you forgot that you dyed your hair a darker color. When faced with this object, the eyes and/or ears send the sights or sounds directly to the amygdala, the part of the brain involved in processing emotions. The amygdala looks at the information it’s been given and sounds the alarm, sending a distress signal to the hypothalamus. (Harvard Health, 2020).

So, next, the hypothalamus takes charge. The hypothalamus is the part of the brain that talks to all the rest of the body via the autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system has two very important parts: the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system. The former is what lights a fire under our feet, so to speak, and triggers the fight or flight response (Harvard Health, 2020).

Fight or Flight:

The term “fight or flight” has been in use since the 1920s (fight or fight or flapper, anyone?). It describes the reactions we exhibit when faced with a threat—perceived or real (Schmidt et al., 2008).

“Accurately or not, if you assess the immediately menacing force as something you potentially have the power to defeat, you go into fight mode. In such instances, the hormones released by your sympathetic nervous system—especially adrenaline—prime you to do battle and, hopefully, triumph over the hostile entity,” said Leon F Seltzer, Ph.D. (Seltzer, 2015).

However, if you take a look at the threat you’re facing and realize that there’s no way you’d ever make it out of that particular battle scratch-free, the body wants to flee (Seltzer, 2015).

…Or Freeze:

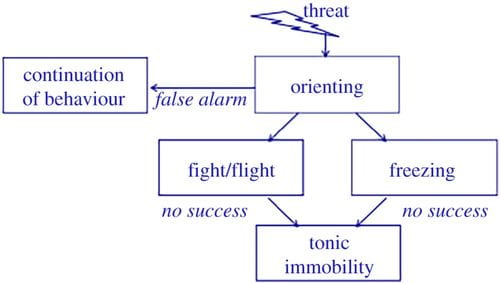

Okay, so both fight and flight make biological sense. But what about freeze? How can a (seemingly) total loss of bodily control when faced with some foe be beneficial? Turns out, it is. Because sometimes, a person can find themselves in a situation where they know they can’t overpower the object of their fear, but neither can they outrun it. That’s when the freeze response kicks in (Schmidt et al., 2008).

Let’s say that—heaven forbid—you’re being attacked. It’s too late to run, and your assailant is stronger than you. In this situation, the freeze response can help you to escape the physical, mental, and emotional pain you’d be otherwise experiencing. And this disassociation can actually preserve your sanity. In such a situation, some of the chemicals our bodies secrete, like endorphins, can act as a kind of painkiller. Also, it’s possible that if an attacker—be it human or animal—feels that their victim isn’t playing along, they might just get bored and stop the attack altogether (Seltzer, 2015).

It’s important to note that the freeze response is a little different from the concept of “tonic immobility,” which is something demonstrated by animals in the wild when they play dead. Playing dead often means “motor and vocal inhibition,” but these two characteristics aren’t necessarily tied to the freeze response (Schmidt et al., 2008).

It’s also important to note that the freeze response isn’t a passive state, or the failure to act. Instead, it’s more like the information gathering stage of fear. The senses take in the situation, the brain develops a plan, and the body prepares to act on that plan in various ways like increasing muscle tone and suppressing pain (Roelofs, 2017).

In addition, studies have shown that people might be predisposed to the freeze response. A study published in the Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry found that, “The majority of items that were more highly associated with freeze included those focused on cognitive symptoms of anxiety (e.g., confusion, unreality, detached, concentration, inner shakiness) as well as fear of losing control” (Schmidt et al., 2008). This is supported by numerous fear studies involving rats; those with a genetic predisposition to anxiety were significantly more prone to freezing than non-anxious rats (Roelofs, 2017).

In the Face of Rheel Fear:

Thankfully, that day with the guy on the couch ended without anybody being harmed. All four of us escaped the house while the intruder continued to slumber, and he only stirred when the cops woke him up (Talk about a rude awakening). But the “what ifs” still sneak up on me, even 12 years later. What if my hesitation put my life at risk? What if my hesitation put my family’s lives at risk?

Betsy Huggett, director of the Diane Peppler Resource Center, went through a similar dilemma. A trained soldier, Betsy was confident that she knew what to do when the base’s sirens went off. However, instead of going to the station as she’d trained to do, she ran. “My training failed me,” she thought at first. “But what I really felt was that I failed. I didn’t feel like my training failed; I failed” (Huggett, 2019).

But we didn’t fail. I didn’t fail. Freezing is part of the natural human reaction, just like fight and flight. It serves a purpose, just like fight and flight. And it has its pros and cons, just like fight and flight. If the intruder had been a light sleeper, too much sound or movement could have awakened him, and then the story I tell as an ice breaker might have had a much more sobering ending.

Still, I have to admit that, if I ever find myself in a similar situation again, I hope I draw the Flight card, so I can get me and mine the heck out of Dodge.