Image from: Paw Paw District Library

By: Sarah Ondriezek

Vaccine-skepticism is nothing new. Objection to vaccines began popping up in the early 1800’s as a response to the English government mandate that children receive the smallpox vaccine. At the time, people raised concerns about the efficacy of the vaccine, mistrust in the government, and the importance of personal liberty. The Anti-Vaccination League and the Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League were both formed in response to the smallpox vaccine, and similar groups (along with anti-vaccination journals) sprung up in the United States near the end of the 19th century.

Despite the fact that vaccines have eradicated deadly diseases for over 200 years, anti-vaccination sentiment has persisted. Proponents of the modern anti-vaccination movement have pushed back against the DTP (Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis) vaccine, the MMR (Measles, Mumps, and Rubella) vaccine, and even vaccine additive, thimerosal. In the last decade alone, parental refusal to childhood vaccination has caused a resurgence of measles and whooping cough. Interestingly, the reasons given for vaccine-skepticism remain similar to those during smallpox: vaccine efficacy, potential risk of harm from vaccines, mistrust in the government (or “Big Pharma”), and personal liberty.

As the world enters its second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel comes in the form of a vaccine. What has largely been lauded as an anecdote to the Sars-CoV-2 virus, has been, unsurprisingly, met with a great deal of distrust from anti-vaccination proponents. The refusal rate for COVID-19 vaccination in the United States has been estimated to be around 25%, placing the threshold for herd immunity in jeopardy and allowing the virus to continue mutating.

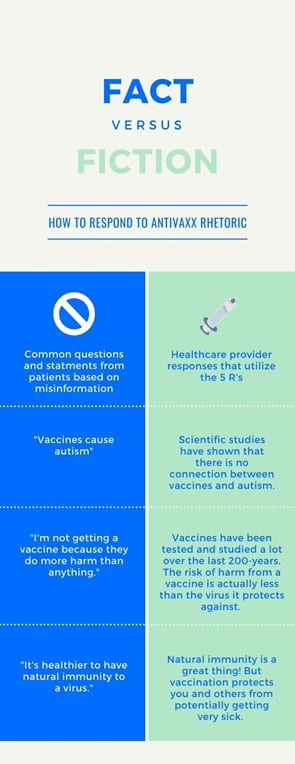

Image from: Flickr

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the CDC, and other, highly visible public health officials/organizations have worked tirelessly in the media to address the importance of COVID-19 vaccination and to dispel misinformation about the vaccine. Everyone continues to work from the same Risk Communication template – how effective is this tactic in persuading the public to accept vaccinations?

The onus to overcome anti-vaccination sentiments eventually falls to health-care providers (physicians, physician assistants, nurses, etc.), who provide face-to-face care for patients. This is an area where vaccine rhetoric experts can offer tips and guidance to help healthcare providers respond to vaccine-hesitant patients in the most effective way.

Compulsion Vs. Persuasion

Historically, ensuring that the public is vaccinated has been approached in two ways: compulsion or persuasion. Vaccination compulsion techniques may take the form of: government ordinance, school or work mandate, or a patient being fired from a physician practice for refusing vaccination. These methods certainly have their benefits (ensuring that everyone who can be vaccinated is vaccinated) but are also accompanied by public backlash and an array of ethical dilemmas. Persuading the vaccine-hesitant is no easy task, as they hold fast to their concerns and beliefs. The difficulty in this task aside, effective persuasion provides the vaccine-skeptical patient with the tools of empowerment to choose vaccination. This method of ensuring vaccine uptake has been growing in popularity as the preferred method for overcoming vaccine-hesitancy. In the field of communications, vaccine rhetoric, under the umbrella of the rhetoric of science and medicine, has emerged as the focused-study of using persuasion to approach vaccine-skepticism.

Vaccine Rhetoric

One of the leading experts on vaccine rhetoric, Heidi Y. Lawrence, Ph.D.. approaches vaccine rhetoric from a material rhetorical approach. In her 2018 article, When Patients Question Vaccines, Lawrence focuses on the difference between objects (matters of fact, stable, known articles) and things (matters of concern, unstable materials that require discourse to understand).

Inlay terms: healthcare providers view vaccines as objects (stable, safe, effective protection against disease that offers high reward with low risk), while vaccine-skeptics view vaccines as things (unstable, potentially dangerous, misunderstood items that are up for debate). Interestingly, there is a lot of reciprocity between objects and things. Things require a rhetorical situation and discourse to become objects; objects require debate and discourse to be understood and recognized as matters of fact.

Using a material approach to develop practical vaccine rhetoric strategies opens the door for successful communication between patient and healthcare provider (actually creating a rhetorical situation in a provider’s office).

Pulling from Lawrence’s 2018 article, and other existing research on the topic, I’ve developed a list of evidence-based tips to assist healthcare providers in addressing their vaccine-hesitant patients.

List of Tips- The 5 R’s

- Refute claims swiftly and directly – offer a counterargument that directly refutes the claim. If a patient says, “I don’t want to vaccinate, because vaccines cause autism,” respond only to that claim. Offer that there is no evidence to support the claim, and that the doctor who originally touted this had his medical license revoked.

- Resist the urge to be pedantic or patriarchal – keep in mind that the patient views the vaccine as a ‘thing’ and not an ‘object.’ Instead, be open, understanding, and use this space to bridge the gap between ‘thing’ and ‘object.’

- Recommendation of healthcare provider – includes the prevention benefits of a specific vaccine and personal endorsement of vaccine. For instance, when recommending the HPV vaccine, the prevention benefit can be stated as, “The vaccine prevents various types of cancer.”

- Respond & identify with a patient – a person’s concerns are very real to them and should not be dismissed. Listening carefully to concerns, using empathy, and identifying with opposing viewpoints opens up space for a dialogue that is respectful and built on mutual understanding. Sometimes, this is all a patient needs to be open to persuasion.

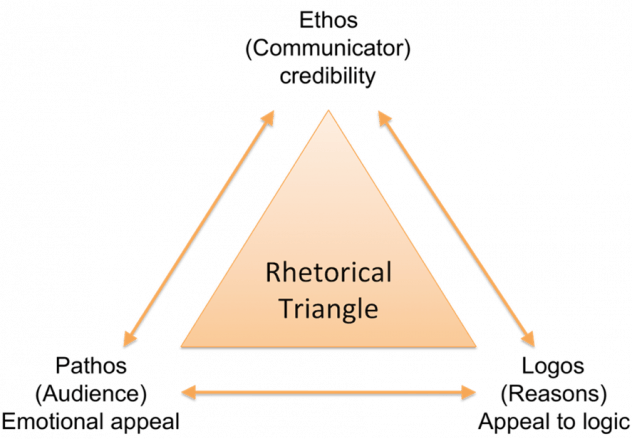

- Remember to use Rhetorical Appeals – Logos, Pathos, and Ethos (see diagram above) should be used in every patient interaction.

Conclusion

The best way to combat vaccine-skepticism is by applying a rhetorical framework based on expert research in the field of vaccine rhetoric. While a great deal of information exists to combat anti-vaccine rhetoric on the internet and in mass communication theory, the first-line response typically comes from a healthcare provider. We must arm our physicians, advanced practice providers, and nurses with the right tools to overcome anti-vax disinformation and rhetoric.