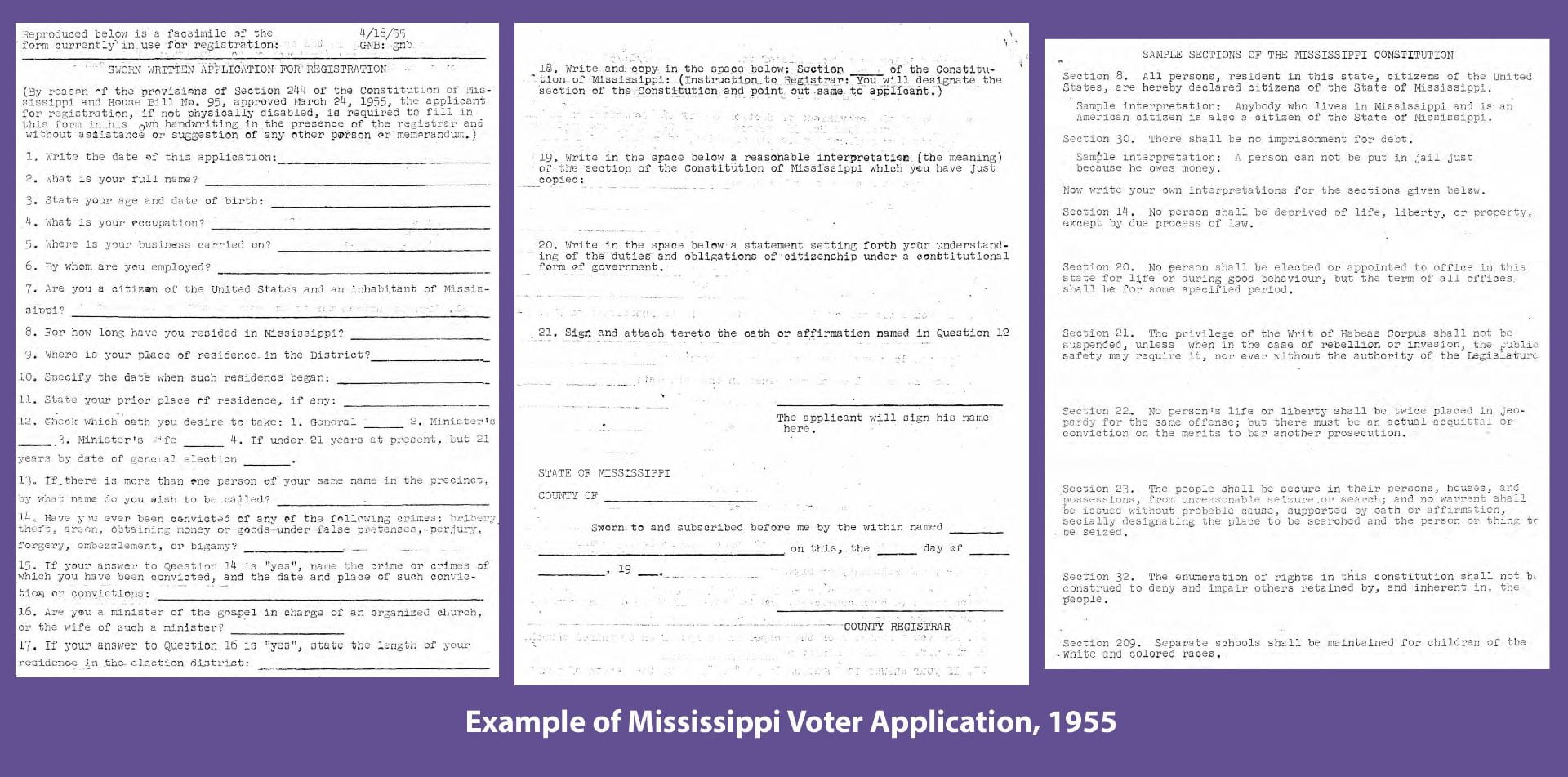

The 1960s is recognized as a pivotal era in American history, when activists in the Civil Rights Movement worked to remove barriers to equality in the voting booth, the workplace, in banking, and more. But, how involved were Chatham students in these efforts? Some might recall that Chatham students joined the marches from Selma to Montgomery in 1965 and organized a campus visit by John Lewis in 1964, but when did they begin to participate in the movement? Using the recently digitized Chatham Student Newspapers Collection from the University Archives, we can explore how a student-initiated exchange program with Hampton University, a historically black college in Virginia, created opportunities for students to better understand racism in American culture and to engage more closely in efforts to dismantle Jim Crow segregation laws in the early 1960s.

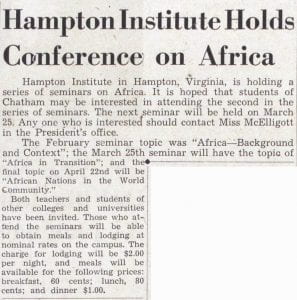

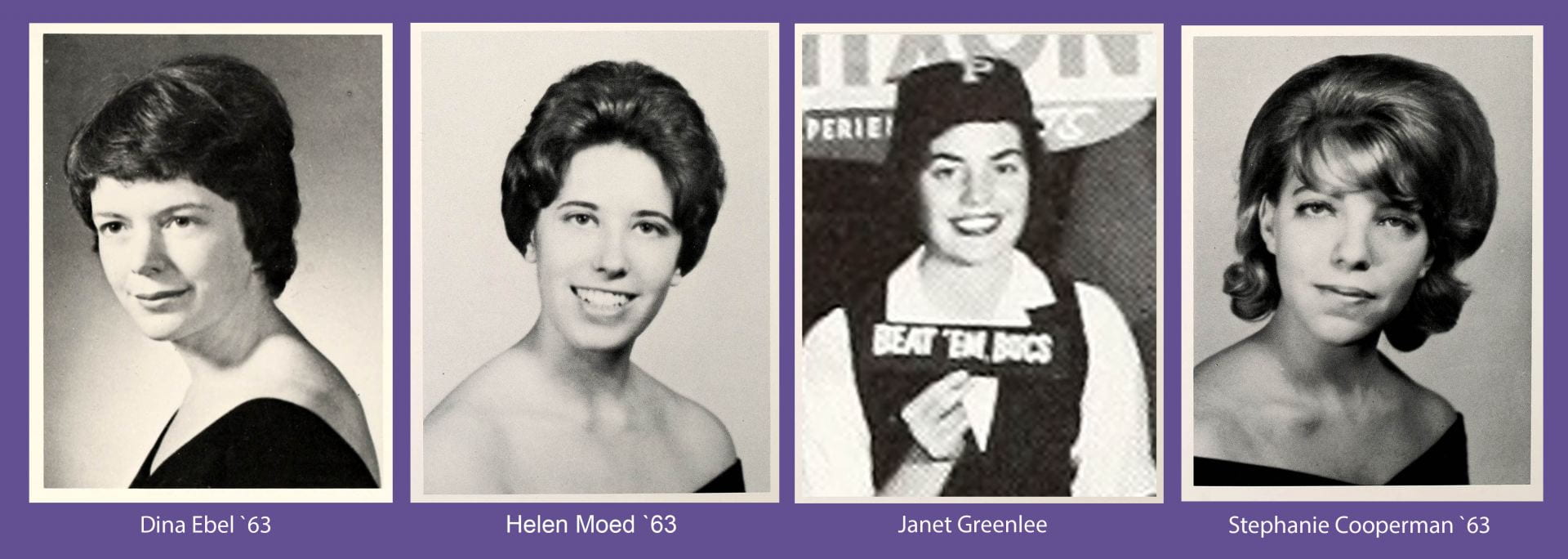

In March of 1961, the Chatham student newspaper (then called The Arrow) ran a front-page article about a seminar to be held at Hampton University (then known as Hampton Institute) on “African Nations in the World Community,” an event that invited interested students and faculty from other schools to attend[1]. Chatham students Dina Ebel `63, Helen Moed `63, and Janet Greenlee accepted the invitation and, upon their return, remarked that they were impressed by the “generosity shown by the students at Hampton” and “their keen interest in international affairs, even with a problem of their own race.”[2]

The three students were highlighted in an article in The Arrow by Stephanie Cooperman `63 as a counterpoint to a sense of general apathy that she felt was affecting the Chatham student population. Cooperman wrote that more opportunities like the seminar at Hampton Institute would help to engage students in the world beyond the campus. She wrote, “Why not allow more of us to learn from actual experience the pain and courage it takes to live as a minority? Why not institute an exchange program, perhaps a week’s duration, with a Southern Negro college?”[3] Ebel, Moed, and Greenlee likewise supported the exchange program idea and wrote, “We had the opportunity and we want others to share our experience. You can’t just talk and write about it; you must live it.”[4]

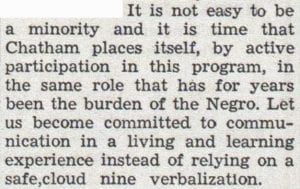

Clip from article by Stephanie Cooperman `63 published on 2/16/1962 “[6]

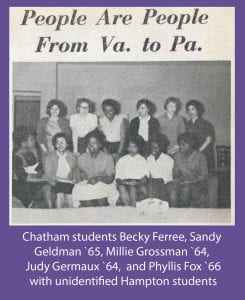

Phyllis Fox`64, one of the five Chatham students to visit Hampton Institute in 1962, wrote in The Arrow that she hoped the program would “help bridge the wide gap of misunderstanding between beings of the same species.” Using poetry to express her thoughts, Fox wrote:

“Every face has known joy and pain;

Every face is wet with the same rain;

The face is only the mask of life

That hides the real human strife.

A person is not a face, but a spirit and a mind

So what matter if his skin is of a different kind?”[7]

Winter of 1963 saw the Hampton-Chatham exchange program promoted in the student newspaper with an article describing it as an opportunity for “discussions on segregation with students who had led or participated in sit-downs and other integration movements in the South” and for insight into “one of the foremost problems of today, that of racial relations.”[8]

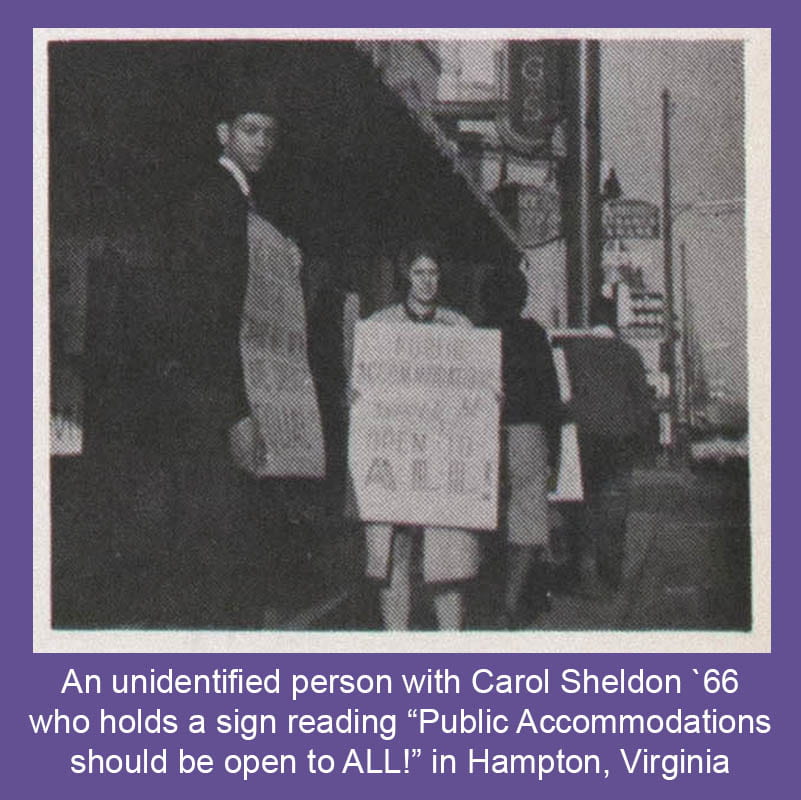

After visiting Hampton Institute that year, Carol Sheldon `66 wrote about participating in a protest and learning about segregated lunch counters and employment discrimination. She wrote, “There is a certain unity about a group of fifty Negroes and three whites who walk into downtown discrimination-ridden Hampton on a Sunday afternoon; perhaps we were partners in fear, since many of us had not picketed anything before and were slightly apprehensive.”[9]

Articles in the student newspaper about the program document a range of responses, with students expressing interest in extending the exchange for a whole semester and also insinuating that the Hampton visitors were given a less than welcome reception on campus.[10]

Articles in the student newspaper about the program document a range of responses, with students expressing interest in extending the exchange for a whole semester and also insinuating that the Hampton visitors were given a less than welcome reception on campus.[10]

Philip A. Silk, an Assistant Minister from the First Unitarian Church, submitted a letter to the editor to The Arrow in which he describes the potential for the exchange program to create “intelligent follow-up projects as aiding groups such as the NAACP or the Urban League.” He continues, “But it can also lead to a feeling that you have done your part, having proved your liberalism in this brief event.”[11] At the start of the 1963-1964 year, The Arrow announced plans to host a bi-monthly exchange column with the Hampton Institute newspaper[12] and efforts to help organize an exchange program between Hampton and a nearby men’s school, Washington and Jefferson College.[13]

The exchange that occurred in the spring of 1965 seems to be the last. Following the exchange that year, Leslie Tarr `68 reported that there was little discussion of civil rights on Hampton Institute campus because the administration “frowned” on student engagement in civil rights demonstrations.[14] That administrators discouraged student participation in civil rights demonstrations is surprising, especially considering that Hampton Institute President Dr. Moron arranged, in 1957, an on-campus position for civil rights pioneer Rosa Parks after her demonstration sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott and she was fired from her job.[15] Tarr also said that Hampton Institute students agree that “It’s the parents who are causing the trouble, and there’s hope for our generation.”[16]

Though it is unclear from the student newspapers exactly why the exchange program ended, it seems that Chatham students remained interested in discussing racism and civil rights issues with members of the Hampton Institute community. In 1966, the Chatham chapter of the National Student Association organized a week-long Civil Rights Forum with an aim to “broaden the exchange of ideas between Chatham students and students of other campuses.” Panelists included students from Hampton Institute, Howard University, Tuskegee Institute and Central State University as well as speakers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[17]

Though it is unclear from the student newspapers exactly why the exchange program ended, it seems that Chatham students remained interested in discussing racism and civil rights issues with members of the Hampton Institute community. In 1966, the Chatham chapter of the National Student Association organized a week-long Civil Rights Forum with an aim to “broaden the exchange of ideas between Chatham students and students of other campuses.” Panelists included students from Hampton Institute, Howard University, Tuskegee Institute and Central State University as well as speakers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[17]

Illustration from The Arrow published on 4/9/1965 [18]

Notes

- “Hampton Institute Holds Conference on Africa,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), March 17, 1961, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25168715.

- Dina Ebel, Helen Moed, and Janet Greenlee, letter to the editor, The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), May 12, 1961 on 05/12/1961, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25168720.

- Stephanie Cooperman, “Student Slams Do-Nothings,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), April 28, 1961, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25168718.

- Ebel, Moed, and Greenlee, letter to the editor, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25168720.

- “Chatham Welcomes Eight from Hampton,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), April 13, 1962, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25168875.

- Stephanie Cooperman, “Chatham Arts On Integration,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), February 16, 1962, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25168871.

- Phyllis Fox, “People Are People From Va. To Pa.,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), April 27, 1962, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25168876.

- “Hampton, Chatham Trade Students for Weekend,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), February 22, 1963, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25168895.

- Carol Sheldon, “Chathamites at Hampton,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), April 12, 1963, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25168899.

- “NSA Board Requests Reply From You,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania),May 10, 1963, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25168901.

- Philip A. Silk, letter to the editor, The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), March 9, 1962, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25168874.

- “Arrow States Policy,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), September 27, 1963, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25168903.

- “Seven to Travel to Hampton, Va.,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), March 13, 1964, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25169448.

- “Five Students Visit Hampton College On Annual 4-Day Exchange Program,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), April 9, 1965, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25169477.

- William Harvey , “Hampton University and Mrs. Rosa Parks: A Little Known History Fact.” Hampton University Website. Hampton University. Accessed January 28, 2021. www.hamptonu.edu/news/hm/2013_02_rosa_parks.cfm.

- “Five Students Visit Hampton College,” https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25169477.

- “NSA to Sponsor Forum on Rights,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), February 4, 1966, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25169521.

- “Five Students Visit Hampton College,” https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.25169477.