Image from: Pixabay

By: Rhiannon Wineland

We all remember Mario, right?

Little plumber with a mustache… overalls… hopping over barrels hurled at him by Donkey Kong… Mario is an iconic video game character. A notable game he stars in is Super Mario 64. The game is simple. You play as Mario and hop into paintings to gather stars in different worlds as you work towards defeating Bowser and saving Princess Peach. While it is a great game, it’s very linear and the player doesn’t get many choices.

But now gamers have choices!

These choices started off small. The Legend of Zelda series, for example, allowed players to rename Link. Eventually, players could choose more detailed dialogue options for him as well. I remember playing Skyward Sword for the first time, for example, and feeling like I could give Link more of a personality. Immediately, I felt morally obligated to choose the nicest options. Was I going to upset this video game character Link was speaking to? Would I break the heart of the character who had a crush on him? This may sound ridiculous, but it made me more anxious while playing the game. I started making sure my dialogue options were as nice as possible.

And games just kept giving me more choices…

I’m not the only one who gets stressed about choices in games! People would reload save points just to redo a conversation in a game because a little conversation can suddenly impact what ending a game gives players! Take the game Detroit: Become Human, for example. The choices will add up and impact other choices. You have the fate of characters in your hands (literally, you’re holding a controller), even characters you think are safe.

Image from: Rhiannon Wineland

Think about reading the suspenseful part of a really good book…

Your eyes will start to skim the pages looking for a clue to your favorite character’s fate, the pages start flying by until you see it! And then you feel a release of relief. Well, the author of the book is obviously skilled in storytelling and building suspense. In this case, you have no control over what happens to the characters here. It’s written and it’s linear. Choices in video games make the story not-so clear cut. That doesn’t mean the developers and writers aren’t good storytellers at all. It just means they’re making the story more immersive. You’ll feel that anxiety of the protagonist in the game, but now you can decide what happens! What will Connor and the Androids do in Detroit: Become Human? Is Ciri going to live in Witcher 3? And sometimes, the fate of a character is dependent on one small dialogue choice. For example, Geralt’s responses to Ciri in Witcher 3 are what decides if she lives or dies. The player needs to make sure the responses they choose fit a certain mood. Personally, I found myself double checking walkthroughs to make sure she lives!

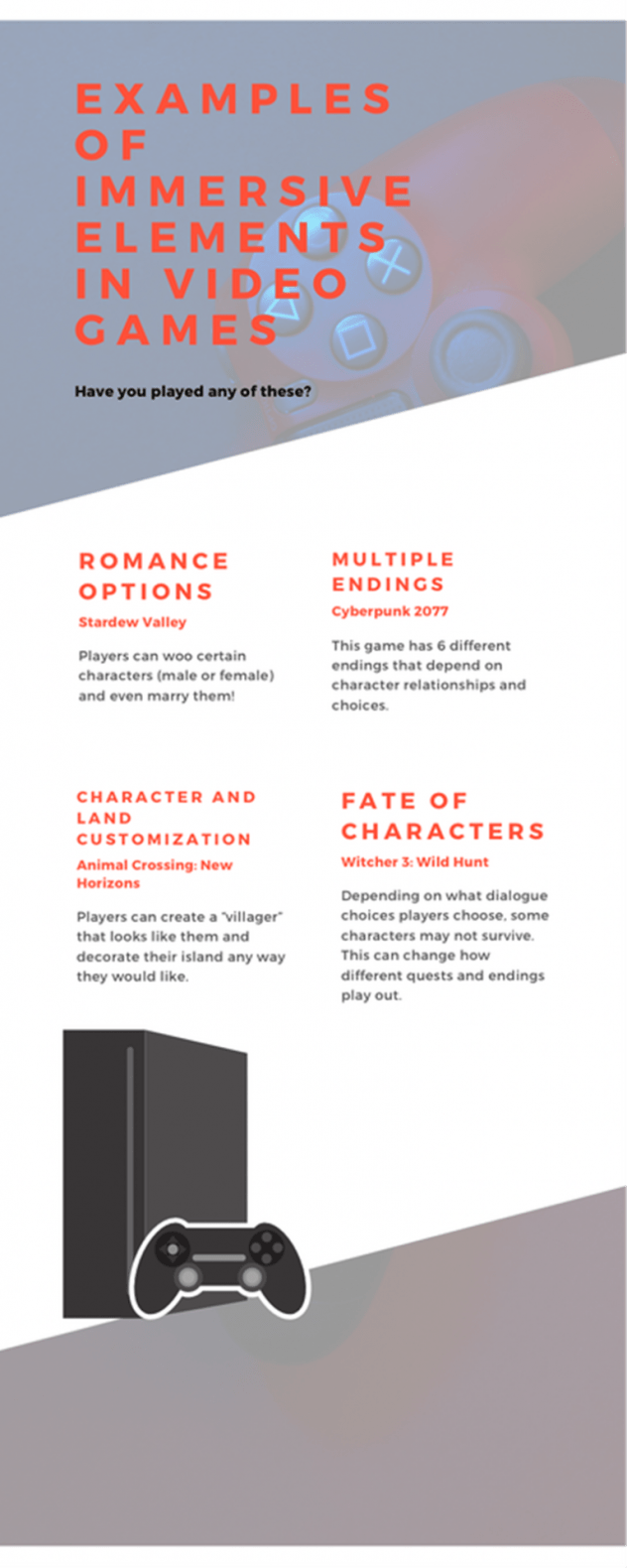

We’re seeing games do this a lot more now!

The stream I discuss in this section was discussion based. As I streamed, people talked in the chat about their favorite immersive elements in video games. Occasionally, I asked questions or had them specify their answers a bit more. To watch this stream, click HERE. Due to the stream crashing a few times because of system updates and Cyberpunk 2077‘s updates, there are several videos in this collection.

Image from: Rhiannon Wineland

Players are loving these immersive elements to the point that it’s unusual to see games without some sort of stake. Let’s use an example that everyone can follow, gamer or not. In 2020, CD Projekt Red released the game Cyberpunk 2077. This game took all these customization elements that most games usually had a bit of and mashed them all together to create what would be a completely immersive experience. The game is in first person point of view so players looking at the world through their eyes. The protagonist is completely customizable with players able to decide on and customize the tiniest of features, their sexuality, background, personality, and love life can be decided on. And it all impacts the game. Your relationships with characters, how you treat Johnny Silverhand (Yes, that’s Keanu Reeves!), and how you navigate the setting decides the ending you get. And there are six endings that you can get. I actually streamed this game, discussed immersive storytelling in video games, and had viewers chime in about what makes them feel immersed in a game.

And you know what’s cool? They all had different answers!

Some talked about the lore of the game, like was there a background to the land, do they talk about the culture of the characters, is this a new, fantasy world, etc. Some just liked tiny decisions like choosing Pokémon to battle with and collect. While I enjoy fast-paced, suspenseful decisions and plot-driven stories, it doesn’t always have to be that way. I’m sure everyone remembers when Animal Crossing: New Horizons came out at the beginning of quarantine in 2020. So many people loved being able to make themselves in the villager customization and design clothes for them. They got to make an island the way they wanted. It was an escape from the scariness that was 2020. It was a happy game that allowed them to be as creative as they wanted.

Image from: Rhiannon Wineland

My friend, Holly, is a huge Wizard of Oz and classic Hollywood fan, so she customized her island to fit that theme. She was kind enough to send me a screenshot of her Yellow Brick Road area.

That’s the beauty of video games.

They’re another form of storytelling that allows a gamer to be immersed in a story in a new way. Developers are always looking for new, innovative ways to get gamers involved, and it always seems like a new release is showing a new way to approach a story. Gamers love choices because it allows us to relate more to the characters and do what we want. Humans love control, so this is perfect. But the amazing part is that this means that anyone who plays a game may get a different experience! This makes it fun for gamers to discuss their experiences and see what else the game has to offer story wise! No game is a bad game and no gamer is less valid. We’re all just leveling up together!

Visit Rhiannon’s Own Blog Here: https://thefantasticrhi.wordpress.com/2021/04/21/choose-your-character-and-more-immersive-storytelling-in-video-games/