Wes Anderson films have a way of turning audiences into Ralphie in “A Christmas Story”. Upon word that another film is going to be released, fans become excited. Doubt lingers in the back of their minds, but when the film is finally released, audiences discover that they end up with the Red Rider BB gun.

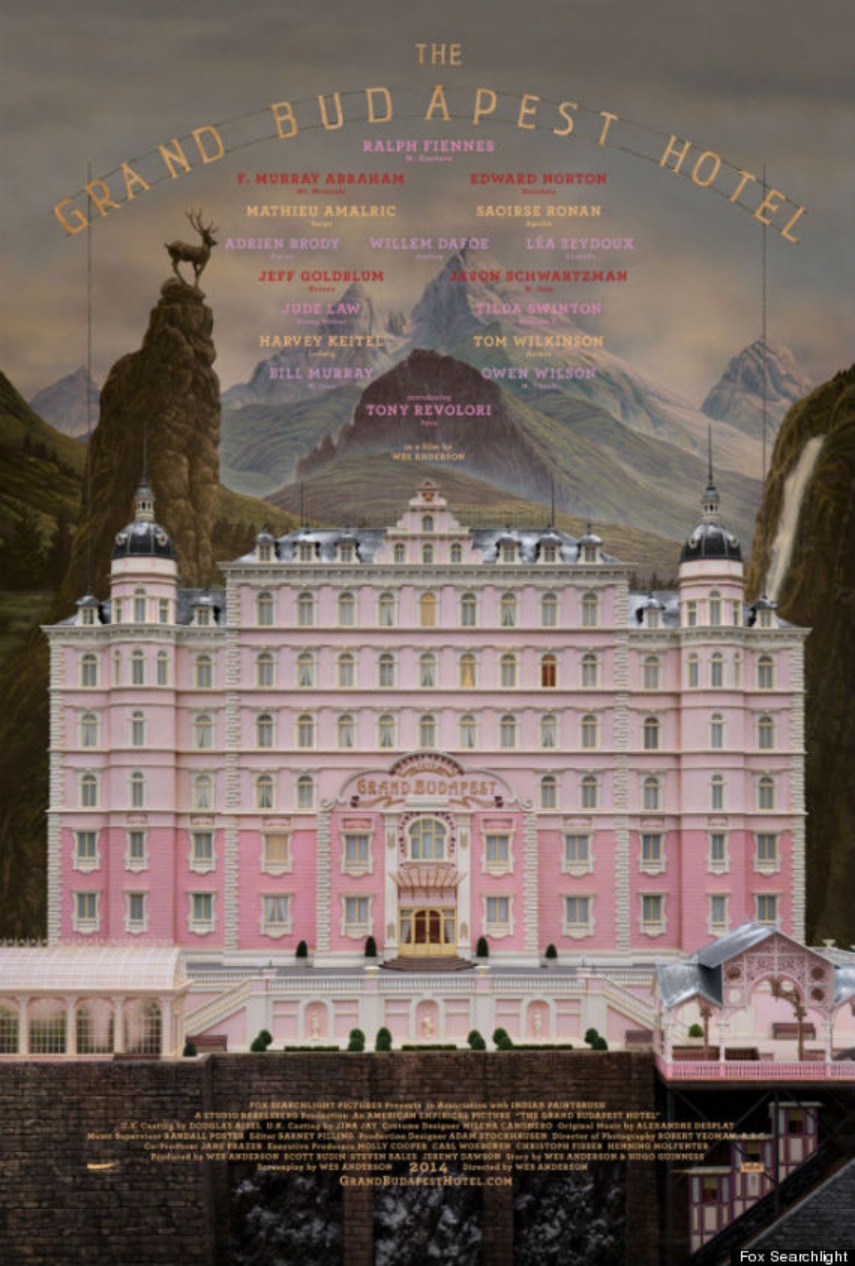

His latest success is “The Grand Budapest Hotel”, centered on the young Zero Moustafa (Tony Revolori) who goes to work as a lobby boy for the eccentric concierge M. Gustave (Ralph Finnes). During Zero’s stay, one of Gustave’s lovers (Tilda Swinton) is found mysteriously killed, leaving him the prime suspect. With a fantastic cast of actors including Adrien Brody, Saoirse Ronan, and Wilem Dafoe, “The Grand Budapest Hotel” is a poignant delight. The film tackles real themes within this zany plot, guaranteed to leave audiences in a bittersweet mood.

Anderson opens his film with a series of frames, starting with a young girl honoring the author who wrote the events behind “The Grand Budapest Hotel”. It then jumps inward to the author as an old man (Tom Wilkinson) explaining his book. After jumping into a flashback of the author as a young man (Jude Law), audiences enter the frame of an older Zero (F. Murray Abraham) as he recounts the events.

Despite the many levels of consciousness, Anderson demonstrates tight control over these frames. He leads audiences further into the labyrinth of this tale, allowing us to become enthralled with the lavish beauty of the hotel. Anderson’s frame also speaks to the construction of the narrative space, with memory affecting the shape of the tale.

Zero’s memories of the Grand Budapest showcase Anderson’s wonderful control of visual representation. Zero’s timeline shifts between memories as a way to neglect the sadness surrounding his love Agatha (Saoirse Ronan). Even without his explanations, the instability of his frames echoes the emotional pain permeating from his memories.

Leaving the frame, Anderson’s technical mastery helps him investigate realistic themes within a fantastical world. The setting in Eastern Europe, the tension of nationalist war, and quick impoverishment of the Grand Budapest makes clear references to WWII and the Soviet takeover. There is a sense of familiarity to this world, but not enough to retain the film’s mystical element. This fluid nature accomplishes two functions: one, it gives audiences the chance to witness the hotel’s enchanting power as Zero sees it. Two, it echoes the speech the author gave prior to the story where he remarks that fiction is composed of nonfictional elements.

“When you’re a famous writer,” he says, “the characters and stories come to you.” In a twist reminiscent of Anderson’s older films, he reminds audiences that, even though the story exists in a fictional universe, the themes discussed are very real. Anderson’s films are known for their unorthodox happy endings following incredible poignancy. He departs ever so slightly from this formula—and succeeds. He then draws audiences back through the frames, leaving us in delighted satisfaction.

In the realm of Wes Anderson films, “The Grand Budapest Hotel” does struggle in packing the same emotional punch. While the film provides a wonderful zany romp, the relationship between Gustave and Zero exist only through implication. The ‘powerful’ moment of the film where Zero confesses that his parents were killed as a result of war seems rushed and surrounded by the comedic situation of the film. However, Anderson’s witty writing and employing the hotel should not deter you from seeing this film. Preferably as many times as the wallet allows.

Rating: 4.5 out of 5.