Denial

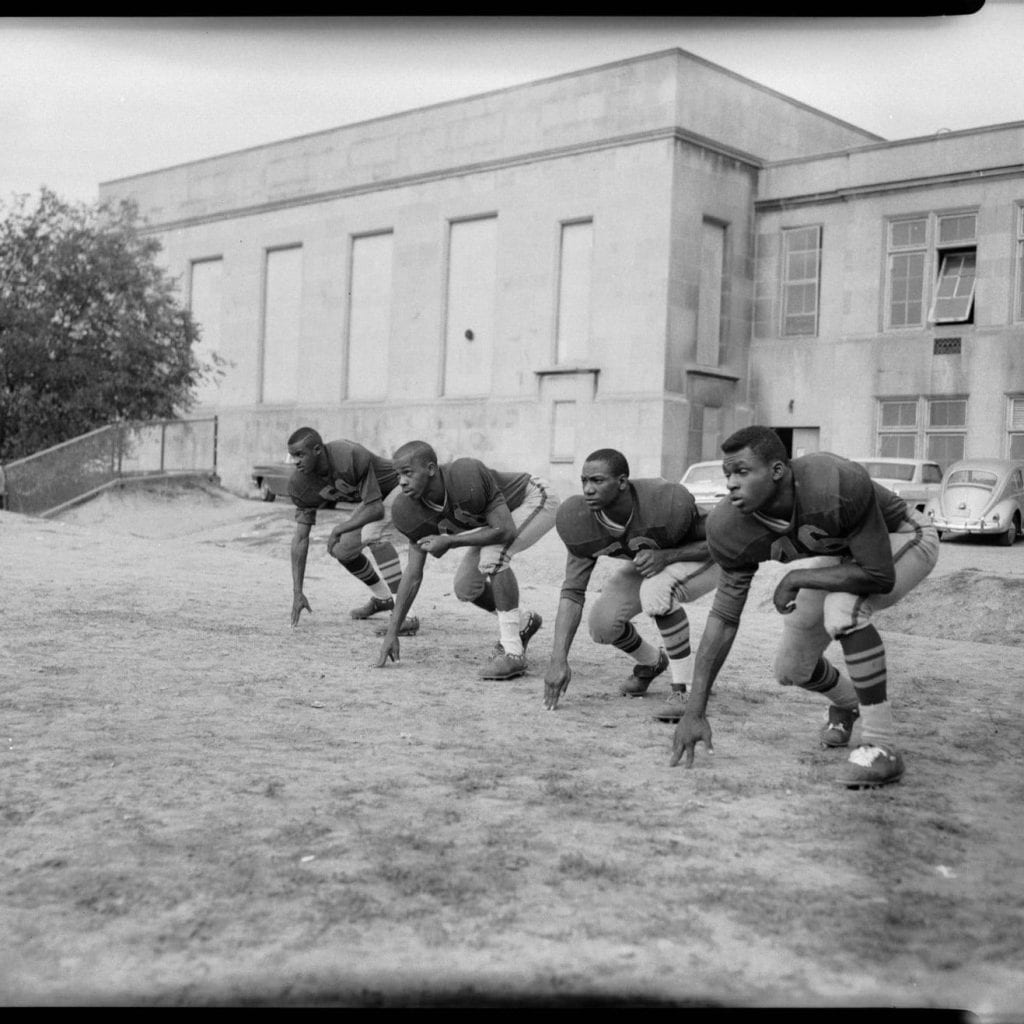

1934. Sophia Phillips Nelson graduates at the top of her class — the first Black valedictorian from Westinghouse High School.

1936. Nelson’s sister, Fannetta Nelson Gordon — a gifted student, scholar, and musician — was poised to be the second. The principal had other plans. “He said, after me there will never be another—the word was not Negro—valedictorian on his watch,” recalled Nelson to the New Pittsburgh Courier.

According to family members, the principal threatened her teachers to change her grades. The music teacher, Carl McVicker — newly hired and fearing for his job — complied. Overnight, her A became a B, and she was denied her recognition.

According to Gordon’s nephew, Nelson Harrison — a gifted musician in his own right — Gordon was “robbed of the valediction at fifteen years of age.”

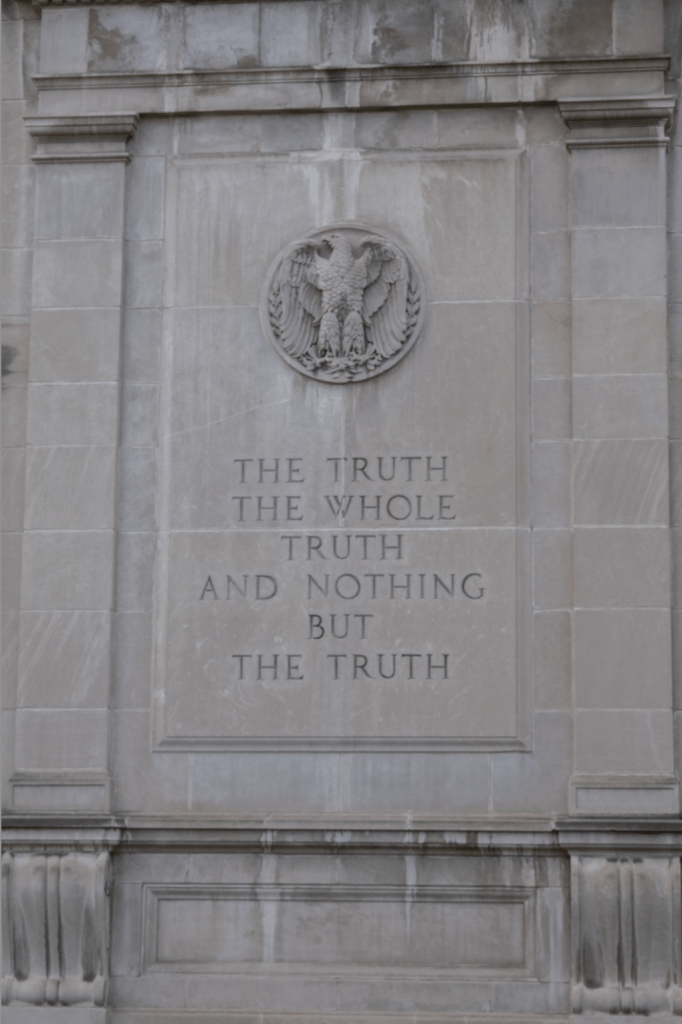

Subsequent analysis by the Westinghouse Alumni Association found clear eraser marks on the transcript — an A replaced with a B.

Success

Fannetta Nelson Gordon would have a prestigious career — one filled with education, music, and family.

After being denied an education in music performance at Carnegie Tech because of her race, she graduated from the University of Pittsburgh with a degree in language. She taught German in the Pittsburgh Public School District for nearly two decades. In 1969, she was appointed as the State Language Supervisor at the Pennsylvania Department of Education in Harrisburg.

She remained a gifted concert pianist throughout her life. Touring with the National Negro Opera Company in her youth. Harrison fondly remembers her playing accompaniment with him as he developed his own musical prowess.

Recognition

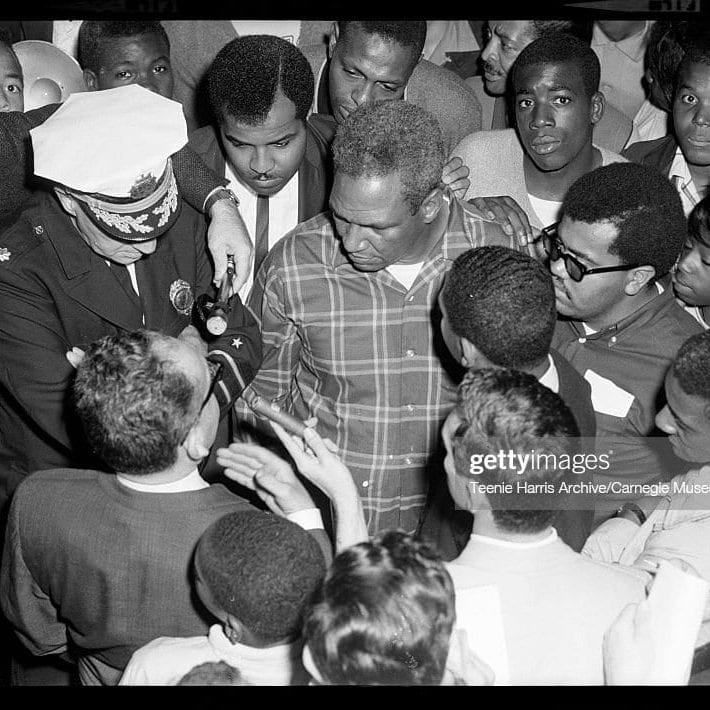

According to Gordon’s nephew, Nelson Harrison, Gordon “was heartbroken ‘til the day she died” because of the valediction denial. McVicker would later reach out to the family, confirming and apologizing for his actions.

She “was heartbroken ’til the day she died.”

In 2011, 75 years after being denied, the Westinghouse Alumni Association posthumously recognized Gordon as the rightful valedictorian. The Pittsburgh School Board also voted to posthumously recognize Gordon as the Westinghouse High School class of 1936 valedictorian.

Though Gordon didn’t live to see the recognition, her sister, Sophia Phillips Nelson believes “her spirit [was] with us. And she appreciates this—I won’t say tardy—recognition.”

Gordon was also recognized with a proclamation from the Pittsburgh City Council and a resolution in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives.