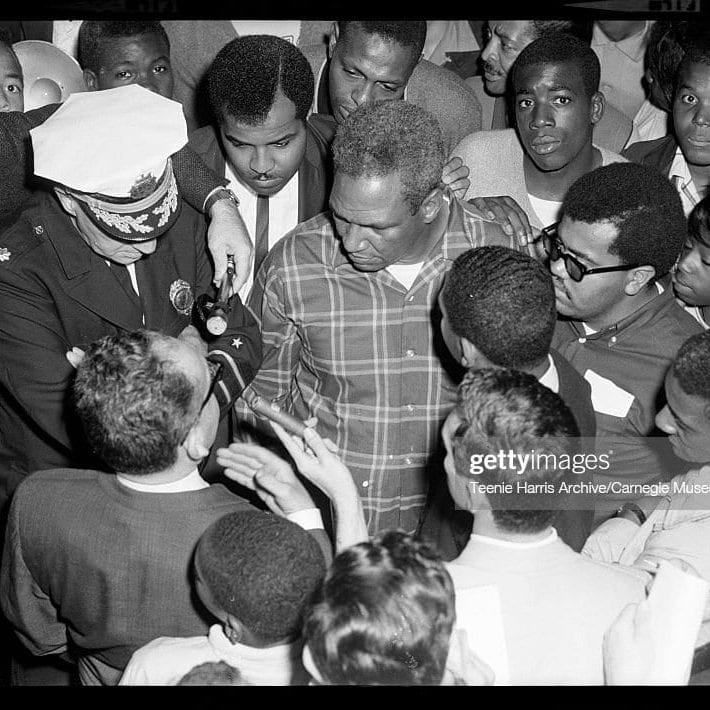

In the 1960s, Dr. Helen Faison served at Westinghouse High School first as a counselor and then as a vice principal. She was remembered by alumni of the 1960s for setting a tone for behavior in the school.

“She was a very tall woman with a very flat voice, but she was always in control, impeccably dressed,” Richard Morris, class of ’69, remembered. “when the bell rang, she would walk from the third floor to the first floor. And the only thing that you could hear in the hallway was her high heels.”

When she got to the first floor, she would sometimes call out someone’s name if they were, for example, running in the hallway, and they would have to go to her office.

“And when you got to the office,” Richard added, “she would hand you a white sealed envelope, and she would say to you, ‘Bring your mama back.’”

She knew many of the parents in the community and was also the Sunday school superintendent at the Baptist Temple Church. This gave her extra leverage over the students. The student who was in trouble would take the sealed white envelope to their mother to open, which would explain why the parent needed to come to the high school to discuss their child’s behavior.

Dr. Faison earned her doctorate from the University of Pittsburgh in 1975 and was the first woman and first African American high school principal in Pittsburgh.

In 2015, Dr. Faison passed away at the age of 91 after an illustrious 60-year career in education. According to the New Pittsburgh Courier, hundreds filled Baptist Temple Church to pay their respects.

Richard fondly remembered how she gently but forcefully set a high bar for student behavior.

“She was a person that she would listen to you, but at the end of the day, if you were wrong,” he said, “you were going to get a white envelope.”